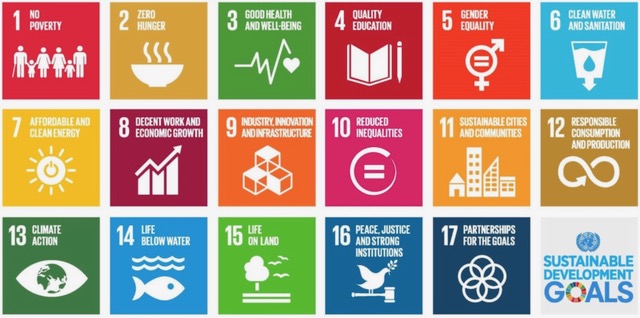

In honor of Global Goals Week, a week where the United Nations and partners come together to bring awareness to accelerate progress to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs, also known as the Global Goals), Black Fox Philanthropy is proud to release this White Paper that shines a light upon how the Goals are being leveraged by organizations on the ground, doing the front lines work to advance solutions to the 17 goals. We’ve profiled giants in the sector such as Splash, Kickstart International, Bridges to Prosperity, Think Equal, READ Global and more to provide concrete examples of how NGOs are bringing about measurable change by working directly with those most affected by the issues the Goals aim to solve.

The Paper was inspired by a session Black Fox Philanthropy produced with Young Presidents Organization at the Skoll World Forum this year of the same name:

From Promise to Practice: Boots-on-the-Ground Perspectives on the UN Sustainable Development Goals

by Natalie Rekstad, Founder & CEO, Black Fox Philanthropy, LLC, B Corp, and Natalie Au, Social Impact Fellow, Wharton Social Impact Initiative

Download the white paper here.

“Ours can be the first generation to end poverty – and the last generation to address climate change before it is too late,” said former Secretary-General of the United Nations, Ban Ki-moon, as the UN announced the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. He asserts, “We don’t have a Plan B because there is no Planet B.”

The SDGs succeed the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of 2000-2015, and are more specific and inclusive, highlighting the intersecting nature of development issues. The SDGs, also called the Global Goals, were adopted in September 2015, and laid out a roadmap through to the deadline of 2030 that aims to “leave no one behind”, including those omitted in the MDGs such as refugees and people with disabilities.

The Goals are gaining traction in overarching ways: in guiding the deployment of billions of dollars in development finance, in building partnerships between public and private sector actors beyond the 193 UN members who unanimously endorsed them, and in providing a framework for advocacy for each of the seventeen goals.

Yet everything we have read on the Goals has an academic lens or high-level view—but what do they look like in practice, on the ground? Now that we are a fifth of the way to 2030, it is crucial to analyze insights collected from development practitioners working at the front lines on how they are leveraging the Goals to help fulfill their promise by 2030. Through telling stories from the field, sharing best practices for measurement, and learning from each other, the development community will become better poised to catalyze change and achieve the Global Goals.

Black Fox Philanthropy is a fundraising strategy firm with a focus on serving international Non-Governmental Organizations (INGOs). As a result of working with INGOs operating in over forty countries, we have a unique view of the landscape and ways in which INGOs are approaching the SDGs from a program and fundraising perspective. We firmly believe that our generation is indeed one that is at a turning point for the world, and participation in its healing is no longer optional. Yet history teaches us that lasting social change is not gifted from above, but rather built through community organizing, engagement, and pressure from below. We also know that achieving the SDGs requires fostering collaboration among many actors, organizing and mobilizing bold funding, learning from grassroots community insights, and measuring progress toward key milestones.

In order to better utilize the SDG framework to achieve the goals, it is essential to examine the impact the SDGs are having from the boots-on-the-ground perspective, and how NGOs, businesses, impact funds, and funders are leveraging the SDGs to up the odds that their promise is fulfilled. Fundamental questions include: How are the SDGs being leveraged to get key initiatives over the finish line in the developing world? How are they generating collaborative relationships with government agencies and the private sector? What challenges are being faced by organizations seeking to leverage the SDGs? Moreover, now that we are a fifth into the timeline of the 2030 goals, what barriers exist to reaching success by that date?

This paper shines light upon grassroots insights from the field. By learning from and supporting boots-on-the-ground perspectives on the SDGs, the work of advancing sustainable development can become even more intersectional, interdisciplinary, and innovative. That, in turn, best creates interventions that can secure effective and lasting change. NGOs have leveraged the SDGs to further their work in various ways: to hold governments accountable, to create community involvement and local ownership, to build cross-sector partnerships, to improve the quality of development data, to guide their mission and vision, and to educate the next generation to be one that treasures global citizenship.

Organizations, governments, and movements have long been working on improving the world in ways that the SDGs and their targets describe. While the SDGs provide a valuable framework, they do not constitute a silver bullet that will unite the world and inspire every person to work towards sustainable living. That requires introspection, informed action, as well as arduous efforts to overcome biases and the lack of infrastructure and funding. Instead, what the SDGs do offer is something that makes this work more tangible and attainable by articulating clear, unifying targets. The varied ways that organizations around the world have utilized the SDGs in the field demonstrate the significance of the explicit and unifying articulation of these goals.

Collaborating With Governments While Holding Them Accountable

While the SDGs are not legally binding for nation-states, governments are expected to be proactive in establishing a national framework for accomplishing the seventeen goals. Respective countries, not the UN, are given the primary responsibility to review and report on their progress. Thus, the SDGs provide a powerful tool for grassroots organizations to hold their governments accountable by leveraging the SDGs to apply pressure for support of their work, as well as hasten the elimination of discriminatory laws.

Women Thrive, for example, worked for twenty years as a global feminist advocacy network with a bottom-up approach to development that had effectively incorporated the SDGs framework into their programming. Through their flagship campaign, “#AchieveSDG5” (Gender Equality), they united over three hundred women’s rights advocates in thirty countries to raise awareness, produce a “National SDG Scorecard”, build national coalitions and advocacy roadmaps, and present outcomes at the UN High-Level Political Forum. The Women Thrive 2016 National SDG Scorecard collected data from 130 grassroots gender equality organizations in thirty-two countries to measure their participation in the implementation of SDGs at national and global levels. Women Thrive has also supported thirty grassroots groups across Sierra Leone, Nigeria, Burundi, Cameroon, and Nepal, to create or formalize existing national-level coalitions on #AchieveSDG5. This process made use of data from the SDG Scorecard to devise evidence-based advocacy, with each coalition writing a National Advocacy Roadmap that spotlights a thematic priority of their choice, such as advancing women’s political participation or eradicating female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/FGC). As a result, Women Thrive was effective in holding governments accountable for implementing SDG5, and in increasing women’s participation in decision-making processes at the national level.

A specific case study further highlights the significance of leveraging the SDGs at the local level. In 2017, Louisa Ono, a grassroots women’s rights advocate from Nigeria, enrolled in Women Thrive’s “Speak the SDGs” and “In The Room” online courses. Louisa was inspired to align her advocacy for women’s political participation with SDG5. One of her first breakthroughs was to mobilize sixty-seven other grassroots organizations to push for a new law on quotas for women in parliament in Nigeria, a law that was passed as a result of the direct pressure. Today, Women Thrive continues to coach Louisa and her coalition in implementing their goal of increasing women’s political participation.

Another instance where the SDG framework has proven effective in holding governments accountable and prioritizing specific development targets comes from Bridges to Prosperity (B2P). B2P is a nonprofit organization that has worked in over twenty countries that partners with local governments to connect their rural last mile through pedestrian bridges.

Their main focus is upon SDG9/Infrastructure; however, it can be argued that without infrastructure, most of the other goals cannot be attained. (It is important to note that many advocates for SDG5/Gender Equality have the same perspective.). At the time that the SDGs were released, Bridges to Prosperity received the results of a randomized control trial study of their footbridge program in Nicaragua, led by economists from the University of Notre Dame, that demonstrated that the return on investment of footbridges is significantly higher than any other community-level investment. B2P now pairs the results of this study with the influence of SDG9 to make a compelling case for the inclusion of a rural infrastructure program in nearly every developing country’s portfolio of development initiatives.

Further, the SDGs framework generates collaborative relationships with government agencies. “[T]he majority of the SDGs require systems-level change—band-aid type solutions aren’t going to make a dent,” says Avery Bang, Founder & CEO of B2P. “Can you build a well for a single community? Sure, but that’s not going to address clean water for the world, or even for an entire country.” Bang highlights that rather than such singular interventions, organizations are beginning to examine the way systems can be improved or, in some cases, completely rebuilt, to “create sustainable, long-term, wide-reaching impact, and that’s naturally going to require government involvement.” To this end, B2P aims to develop partnerships with local government agencies to ensure that their programs not only advance sustainability but are sustainable themselves.

Creating Community Involvement And Local Ownership

The SDGs highlight the importance of co-creation with local communities in any kind of development intervention, and this emphasis has not been found in previous development agendas. Splash, an NGO centering its efforts on SDG6 (ensuring availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all), appreciates the way the SDGs underscore the significance of human-centered design and producing interventions catered to each local environment rather than adopting a one-size-fits-all program.

Splash puts sustainability at their core, using engaging design to encourage the use of water stations and improved toilets. A 2015 UNICEF report states that thirty to fifty percent of WASH projects fail in less than five years. “There are absolute graveyards of these failed WASH projects globally because people weren’t thinking about design,” says the Founder of Splash, Eric Stowe. “They were not thinking about the usability, the volume of kids, or withstanding the local environment—from natural disasters to vandalism.”

Further, Splash emphasizes community ownership as a priority. The organization recently achieved a major milestone ten years in the making—reaching every orphanage in China with clean, safe water. They have benefitted over 100,000 children across 1,100 orphanages around the country. With this goal complete, their next goal is to transition the project to local ownership. “The intent should be to scale the solution, not the organization,” Stowe says. “We believe we can exit China in the next two years. The Chinese government can take this on in perpetuity. Now that we’ve created the ecosystem, that’s possible and affordable. We’re really excited about that.”

Another example of sustainable interventions designed to cultivate community ownership comes from B2P. Through its training partnerships with local government departments, B2P is “building talent locally so that knowledge and experience are shared,” Bang says. “We’re thinking about working with national transportation and public works departments to include rural last mile connection in their strategic infrastructure plans for years to come—not only the building of footbridges but the maintenance of them, as well,” Bang explains. “We’re building training for the design and construction of effective, low-cost structures into civil engineering and vocational programs.” By collaborating with the local government in this way, B2P contributes to a systems-level change in the present and further develops relevant skills in the local community to continue this change in the next generation.

Building Cross-Sector Partnerships That Amplify Progress Towards The SDGs

Aside from encouraging relationships with the local communities in which international NGOs operate, the SDGs also galvanize cross-sector partnerships between development organizations. For example, Days for Girls, a global menstrual health and education movement, works through the lens of the SDGs when assessing and fostering partnerships as well as when raising funds. The organization’s International Enterprise Director, Sarah Webb, finds it useful to reference the SDGs in her presentations to current and potential donors, partners, policymakers and volunteers around the world.

“The SDGs provide a helpful framework for organizations to evaluate intersectional ways to partner with communities. It’s helped us create a framework for evaluating partnership growth,” she says. “Our partnership with Splash in Nepal is a good example. Splash is working with schools in Nepal to provide water sanitation systems, and we brought in our menstrual health solutions last year. By working together, our combined efforts were able to make more progress on more of the SDGs than we could have as separate projects.”

In addition, we also find an effective partnership in Communities Thrive, a project between Rural Education and Development (READ) Global and IREX. READ is a nonprofit with a scalable and low-cost model: community members establish community centers that provide education, employment, and health services while incubating new businesses that hire locally and generate the revenue required to cover the operating cost of each center. IREX, on the other hand, is a nonprofit with an annual portfolio of $90 million and that has worked for decades in over a hundred countries in scaling grassroots initiatives. Together, they aim to multiply their impact “at a time when many nonprofits implement duplicative efforts”.

Developed over the last twenty-five years, READ’s locally-owned and financially self-sustaining model has reached 2.3 million people through one hundred community centers and 195 for-profit enterprises that support the centers. Through the Communities Thrive partnership, READ and IREX aim to scale READ’s interventions in the next five years by opening one hundred new community centers in Nepal, India, and Bhutan, as well as one hundred new businesses that will generate revenue in support of the centers. By collaborating with their complementary expertise and resources, READ and IREX are able to amplify progress in multiple SDGs in a way that would not have been possible had they continued their work separately.

Notably, the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda has thus incorporated into the seventeen SDGs something that multiplies its own effect: the necessity of partnerships for the goals, a core ingredient to sustainability that grassroots practitioners have long known to be true, is instituted as an SDG in itself (SDG17). As the above insights from the NGOs working on various issues and in various countries indicate, this assertion of the need for partnerships has served well to accelerate change on the ground.

Improving The Quality Of Data And The Process Of Monitoring And Evaluation

For each of the seventeen goals, specific targets and detailed indicators with which to measure progress are listed, and this advances the relationship between data and development in two ways: first, the indicators provide a guideline for what kind of data to collect; second, the data collected allows stakeholders to improve their interventions and raise more funding with evidence-based claims. As the World Bank report, “Open Data for Sustainable Development”, highlights, the insight gained from open data is a key resource for fostering economic growth and job creation; improving efficiency and effectiveness of public services; increasing transparency, accountability, and citizen participation; and facilitating better information-sharing within the government.

The importance of this two-way relationship between data and development was articulated even before the SDGs were announced in 2015. Before launching the SDGs, the UN convened a High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda, and the Panel emphasized the need for a “data revolution” to strengthen progress. As a result, the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data (GPSDD) was established to harness the data that is being generated at “unprecedented levels of detail and speed” due to advances in technology. The GPSDD operates on various levels: from the national level of developing partnerships with governments to use data in achieving national priorities for change, to the more micro level of collaborating with stakeholders to build global data principles and protocols for sharing privately held data, to the technical level of harmonizing data specifications and architectures. As we move toward a more data-driven world, it is critical to ensure that we are making data work for development by collecting reliable data that is able to inform and improve interventions.

Beyond the unprecedented sophistication of volume and types of data, it is also essential to collect and process data through an inclusive lens. While the word “data” may hold connotations of objectivity, the reality is that both the “what” (what kind of data to collect) and the “how” (what kind of experiment to conduct, what kind of questions to ask in a survey, etc.) of the data collection process may be biased and reflect current inequalities—and perhaps even perpetuate them. For example, global education enrollment data is not disaggregated by sex at the upper-secondary level. “While huge numbers of girls are missing out on the final years of their secondary schooling, they are not even being counted,” says Nora Fyles, the Director of the Secretariat for the United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative (UNGEI). Without such data, it is difficult to design effective interventions, let alone conduct reliable monitoring and evaluation to improve them based on their results. Moreover, the women’s empowerment nonprofit Starfish emphasizes that while many metrics and data tools focus on high-level change (aggregated data at the national or regional level) or micro-level results (individual studies of grassroots projects), there is a dearth of effort to link the two meaningfully. With regard to the thousands of existing studies on interventions to further gender equality and women’s empowerment, Starfish points out that “the vast majority of this work provides quantitative data, which, while useful, offers only a partial picture.”

Aiming to bridge this gap, Starfish and the collaborative group of the Posner Center for International Development are developing a tool that “adequately assesses grassroots work in light of the specific goals of SDG5.” The project partners worked together to select the SDG5 indicators they have in common, reviewing them to see how they would complement each partner organization’s existing evaluation mechanisms. Starfish states, “What emerged was a set of questions that relate to the SDG5 indicators, but that center on a woman’s perception of her ability to influence those indicators.” Importantly, each partner organization will translate the tool not only by language, but also to fit the organization’s “current evaluation efforts, and the context and cultures in which they work.”

This example demonstrates the power of leveraging the SDGs framework to design a data collection process that is inclusive and sensitive to culture and context, yet at the same time easily shared across organizations and combined to potentially influence change at the regional or national level. By collectively aligning the impact measurement of multiple grassroots initiatives to the high-level SDG agenda, this monitoring and evaluation tool begins to address the gap between micro and macro data in development. Further, because this tool explicitly uses the common language of the SDGs, it could be effective not only in internally evaluating program effectiveness but also in externally sharing results between partners or with funders.

Guiding Mission and Vision

Stories matter: They “shape how we understand the world, our place in it, and our ability to change it”. Indeed, a tangible impact is crucial—but one of the most critical roles the SDGs play is that of informing mission and creating a vision. Not merely weaving the mission statements of grassroots organizations, but also instilling in individuals a sense of a mission—of something ambitious, idealistic, yet probable; of a collective story that unites and encourages systemic change. How are organizations on the ground making use of this aspect of the SDGs, and have they been successful?

KickStart International, an NGO with the mission to “lift millions of people in Africa out of poverty, quickly, cost-effectively and sustainably by enabling them to make more money”, uses the SDGs framework not only to guide the different aspects of their programming, but also to incorporate themselves into part of a bigger, collective movement made up of many other entities around the world working towards the seventeen goals.

Likewise, Global Grassroots leverages the SDGs in the field application of their mission to “catalyze women and girls as leaders of Conscious Social Change in their communities”. An example can be found in their training and support of women community leaders to claim access to water. For Global Grassroots and the local women change agents they serve, ensuring that women are at the forefront of water infrastructure development is one of the most significant steps in making progress on multiple SDGs, including poverty (SDG1), health and wellbeing (SDG3), education (SDG4), gender equality (SDG5), clean water (SDG6), decent work and economic growth (SDG8), and peace, justice and strong institutions (SDG16). By making explicit the link between women’s control of water to the advancement of multiple SDGs, Global Grassroots builds a more commanding case for support for their work: this becomes not only intrinsically valuable (ensuring women have access to clean water is, in and of itself, important) but also instrumentally crucial (women’s control of water advances sustainable development in so many other areas). The SDGs framework thus situates the localized work of Global Grassroots against the bigger picture of the global movement, aiding not only in the organization’s programming efforts but also in its fundraising capabilities.

Thus, the SDGs schema also provides a unifying language and story for philanthropists. For instance, Pencils of Promise, an INGO working on global education, connects stories from the field to SDG4 (Quality Education) in order to advance philanthropic relationships. Most recently, the organization used this method to raise $1.25M USD from The Pineapple Fund, a millennial-driven, bitcoin-financed charity.

This ability of the SDGs to tell a collective human story is perhaps one of the most invaluable features of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Educating The Next Generation To Be Global Citizens

Beyond shaping mission, organizations at the front lines of development are also integrating the SDGs into education to ensure that the next generation need not retroactively define sustainable development goals and alter their behavior to meet them; rather, the hope is that this generation will grow up understanding the world through a lens of global citizenship that informs its every act.

For instance, Think Equal, an organization that produces a comprehensive and formal curriculum for social and emotional learning (SEL) to be incorporated into schools, was designed to directly address nine of the seventeen SDGs. Under the guidance of advisors with expertise ranging from education to human rights, to psychology, to neuroscience, and more, Think Equal is constructing and delivering what they call the world’s first SEL curriculum for a subject named “Equality Studies”. Other than comprehensive lesson plans spanning weeks, focused on interactively teaching each SDG to children aged three to five, Think Equal has also partnered with Sir Ken Robinson to create an educational picture book that encourages children to brainstorm their own ideas on how to achieve the global goals. Sir Ken Robinson previously wrote for the videos of Project Everyone, a communications campaign that seeks to make the SDGs famous worldwide to maximize the chances of them being achieved.

By bringing together all the various development challenges and intervention efforts in the world under the uniting and simple framework of seventeen goals, the SDGs present what may otherwise seem overwhelmingly complex and insurmountable as a series of targets that we could accomplish, step by step. As Sir Ken Robinson’s Think Equal picture book explains, “[We] are causing these problems. So, we can fix them too, if we all work hard together to solve them. The good news is we already have a plan. A plan to protect the planet and make the world safe and fair for everyone. We have the Global Goals.” More than distilling the world’s challenges into actionable steps that even children could comprehend and be inspired to contribute to, such a framework also gives adults a coherent and comprehensible – and, perhaps most importantly, optimistic – approach to the array of development challenges we face today.

What’s Next?

Equipped with such valuable insights, what can we do next? Analyzing the work of all the entities mentioned above, three main challenges (and thus, opportunities to do better) emerge in the path to achieving the SDGs by 2030: 1) significantly increasing the amount of private capital in development funding; 2) improving the design and analysis of data collection; 3) organizing initiatives that amplify community voices and mainstream the development agenda such that the ordinary person also feels compelled to contribute to a more just and sustainable world.

First, more capital from the private sector is crucial to financing sustainable development. “Official development assistance (ODA) and philanthropic funding are never going to be enough to achieve the SDGs within fifteen years,” says Avery Bang of B2P. Indeed, in 2017 the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development reported that achieving the SDGs will take between $5 to $7 trillion and that the investment gap in developing countries is approximately $2.5 trillion. Meanwhile, the OECD reports that ODA totaled only $146.6 billion in 2017—”one order of magnitude smaller than the needs.”

To move forward, blended finance models such as impact investing as well as partnerships with private sector actors that go beyond the notion of “corporate social responsibility” are needed. “Even beyond getting funding from the private sector, it’s important to think about how to partner more effectively with them,” explains Erica Kochi, Co-Founder of the UNICEF Innovation Unit. “How can we deliver social good through the private sector? How can the private sector do more than corporate social responsibility as an afterthought, and instead have social good built into their practices, products, and services from the very beginning?” To this end, UNICEF Innovation evaluates emerging technologies in the two-to-five-year horizon to find possible areas of collaboration with the private sector “to find shared value in this future space”. Through the UNICEF Innovation Fund, Kochi also co-leads investments in early-stage solutions (many of which are for-profit) that demonstrate potential to improve children’s lives. “Developing countries are showing increasing appetite for technology and business, so many private sector actors are boosting their focus there,” Kochi explains.

Second, development data needs to be more accurate, reliable, and connective between grassroots projects and high-level initiatives. Especially critical is “gender data”, data that is disaggregated by sex (e.g. data about primary school enrollment rates for girls and boys). As many development practitioners have found, SDG5 is tied to every other SDG, and gender data will help in interventions that may not be addressing issues directly related to gender equality and women’s empowerment. As stated by Data2X, an initiative led by the UN Foundation to improve the quality and availability of gender data, this type of data is “critical to determining the size and nature of social and economic problems, the causes and consequences of those problems, how to design policies to combat them, and the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of those policies.” Without access to high-quality data and proactiveness in linking results from micro and macro interventions, effective monitoring and evaluation cannot be carried out. In turn, development efforts will be unable to maximize their impact, regardless of how passionate for change the development practitioner may be.

Third, and relatedly, the Sustainable Development Agenda must not be the work of development practitioners only. In order to achieve the SDGs by 2030, it is vital to amplify voices within local communities, as well as to mainstream the SDGs. As B2P’s Bang asserts, “A culture of concern and a perspective of shared humanity, across all sectors and across borders, will be necessary because that’s the only way we’ll start building social improvements into everyday transactions, private investment, and global business.” Initiatives like Project Everyone and the SDG Action Campaign have so far delivered positive results in SDGs mainstreaming by working with influencers, creating viral Internet content, and harnessing emerging technologies like virtual reality to produce media for advocacy and education that generates interest outside the development circle.

Programs that proactively source, fund, and support youth voices and community-led development interventions also increase our likelihood of achieving the SDGs. For example, Ideas for Action (I4A), a partnership between the World Bank Group and the Zicklin Center for Business Ethics Research at the Wharton School, is a knowledge platform that connects young development changemakers around the globe. Each year, I4A hosts an annual competition for youth all over the world to design ideas for financing the SDGs. Creators of the best proposals they receive support from Wharton students and staff, as well as the World Bank, in the implementation of their idea, usually local to their own community. Through such initiatives, the vital voices of youth leaders and community members are heard by high-level entities such as the World Bank, and this again ups the odds of achieving the SDGs by 2030.

To conclude, grassroots advocacy to demand more from local governments have existed long before the declaration of the SDGs. Yet what the SDGs framework has done is to create a detailed roadmap with clear-cut targets to be reached within each goal that holds governments accountable not only to their people but also to the UN and the global community. This better encourages the mass mobilization of, as well as collaboration between, different grassroots organizations working on differing but intersecting issues that require systemic change. As the inspirational story of women’s rights activist Louisa Ono demonstrates, this ability to band together various causes under one expansive yet concrete set of goals creates greater opportunity for tangible change.